Ancient Ships: The Ships of Antiquity

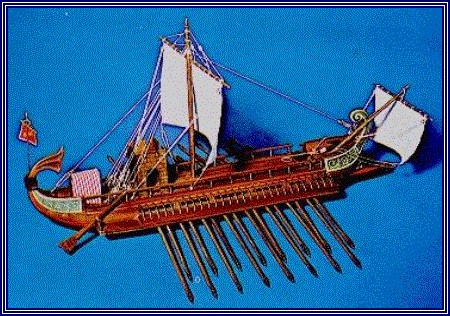

Roman Galleons

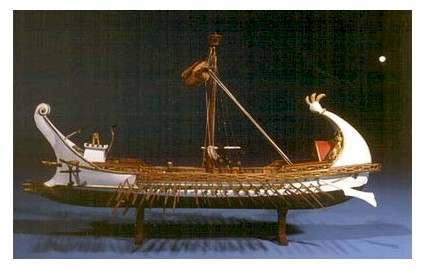

The Marsala Punic War Ship 240BCE

Model Length: 24-1/2" (623mm) Scale: 1/30

provided by Hobby World of Montreal

A typical Roman war ship of the first Century

B.C. this Bireme was driven by two rows of oars. Out riggers stabilized

the ship and the whales protected the hull from the protruding bows

of enemy ships. While fast under oar, this type of vessel capsized

easily under too much sail. This ship was built with plank on bulkhead

construction.

The model is a kit that has been recently

updated. Panart's double-planked hull features laser cut wooden

components. The bow and stern sections, which used to be made of

plastic, are now laser cut out of wood. The oars now come pre shaped

but still require assembly. The fittings are of wood and metal.

Cotton sail clothe, rigging. The silk tent for dignitaries or officers

and the imperial standard of Caesar are silk-screened. Instructions

included.

The crew of a liburnia consisted

of about 50-80 oar-men (remiges) and a unit of about 30-50 marines,

depending on the size of the ship. Liburnias were used everywhere

in the roman empire, for e xample on the Nile, Rhine and Danube

rivers. Compared to the fighting value ot the earliest warships

with only one row of oars-men, the liburnia was a more powerful

ship especially when ramming an enemy ship. With a closed

deck it could take more marines as any other ship this size for

the purpose of hand to hand combat helping insure a victory when

fighting at close quarters with a ship of the same size.

The crew of a lubrnia consisted of about 50-80

0ar-men and a unit of 30-50 marines. each varied based on the size

of the ship. These ships were used extensively everywhere in the

Roman empire for example on the Nile, Rhine and Danube-rivers. Compared

to the fighting-value of the earlier warships with only one row

of oar-men, the liburnia was a more powerful ship, especially when

ramming an enemy ship. With a closed deck, it also could take more

marines ("manipularii" in latin) as any other nation's

ship of this size.

1st Century Roman Galleon as depicted on

a Roman Coin

Prow of Ship depicted on a Roman Bronze Coin

Coin commemorating the naval victories of

Pompeius Magnus During the Mithri dates Wars

The Historic Context of this coin.

THE FIRST TRIUMVIRATE, 60-54 BC

Pompeius Magnus with Julius Ceasar and Crassus

After 30 years of increasing pressure to Roman

shipping and trade from the Greek Empire in the East. In 67, the

tribune Roman Aulus Gabinius forced a bill through the popular assembly

awarding Pompey command of the campaign against the pirates in the

Eastern Mediterranean. Other commanders had been in Anatolia and

the east for some time attempting both to destroy the pirates who

were damaging Roman shipping and trade, and to make a dent against

the ever-troublesome Hellenistic Greek king, Mithridates IV who

ruled out of Pontus.

Mithridate IV had 400 ships of his own in the water

and was supporting the activities of piracy against Roman shipping

and trade in the Eastern Mediterranean.

Portrait of Mirthradates IV Front and Pegasus and

Laurel Wreath Back, tetra - drachma, minted with silver in Pontus

Portrait of Mirthradates IV Front and seated

Athena Back drachma, minted with silver in Pontus

See references to the Mythridatic war. "Mithridatic

War"

"Mithridates

& The Roman Conquests in the East, 90-61 BCE." Translated

selections from Appian and Plutarch with introductory material (Paul

Halsall).

Pompey received his military command in the face

of entrenched political opposition. It was the sheer scale of the

military forces to be allotted to Pompey which created the primary

concern to the Roman Republic and for many it seemed to be a clear

danger signal that Pomp e y may o btain to much power and influence

in the Eastern Empire. Although it was apparent the military campaign

in the east was needed to protect Rome's shipping and trading interests

the assignment of so much military power into the command of one

individual was not a political ly popular position.

THE GREEK KING MITHRIDATES AND THE PIRATES, 67-62

BC

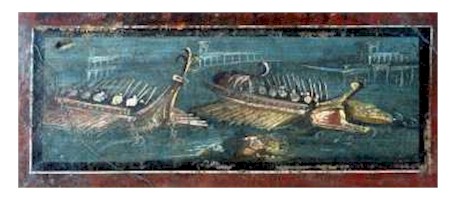

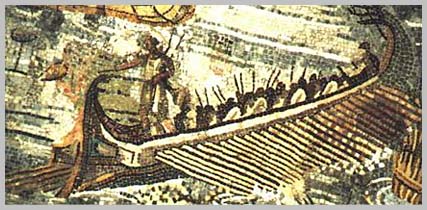

Roman Galleons in Wall Fresco From Pompeii 70 AD

Julius Caesar was one of the Senators who supported

Pompey's command from the start and was later to form strong family

and political alliances with Pompey. The command to conduct the

eastern campaign gave Pompey sole authority over the entire Roman

naval forces available in the Mediterranean and beyond. His leadership

role set him above every other military leader in the E astern

Roman Empire. In three short months (67-66 BC), Pompey's forces

literally swept the Mediterranean free of the pirates. Pompey's

successes helped him become the republic's hero of the hour.

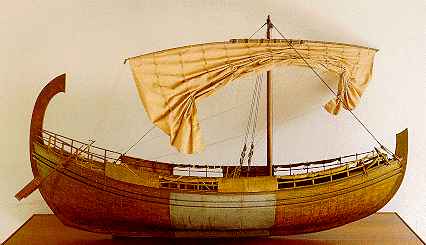

Model of Shipping and Trading vessel of the Mediterranean 1-3 centuries

BCE

Pompey returned to Rome in December

62 to celebrate his third and most magnificent Triumph during his

successful military campaign s in the Eastern Mediterranean .

He was now at his zenith, however by this time Pompey had been largely

absent from Rome for over five years and a new star had arisen with

the young Julius Ceasar. Pompey had been busy in Asia when a young

Julius Caesar pitted his political will against that of the Consul,

Cicero, and the rest of the Optimates. Pompey had been occupied

while new political alliances were being formed in Rome during his

absence.

After returning to Rome, Pompey

dismissed his military command, disarming his political opponents

of grounds for their worries that he intended to spring from his

conquests into domination of Rome. Pompey was a supreme political

as well a s military tactician; he simply sought new allies and

pulled strings behind the political scenes to assert his political

will . However his political opponents failed to affirm his magnificent

victories and the conquering and settlement of the Eastern Roman

Empire.

Contemporary Painting of Roman Galleon from walls of Pompeii

To view additional images of Roman Ships please visit. GALLERIA

NAVALE

Pompey found his political opponents prevented

him from to delivering on the promises of the assignment of public

lands to his veterans after the war. Pompey's political maneuverings

suggest that, although he toed a cautious line to avoid offending

the conservatives, he was increasingly frustrated by Optimate reluctance

to acknowledge his solid military and political achievements. Pompey's

ambition to fullfill his promises and the political frustration

s brought about by the opposition of the Optimates would force

him into new and strange political alliances.

POMPEY BECOMES A MEMBER OF THE FIRST TRIUMVIRATE, 60-54 BC

Pompey found he was unable to deliver on the promises

he had made to his veterans for the allocation of public lands.

Although Pompey and Crassus distrusted each other both felt aggrieved

in 61 BCE ; Crassus' tax farming clients were being rebuffed at

the same time Pompey's veterans were being ignored. Caesar who was

six years younger than Pompey and had just returned from service

in Spain ready to seek the Consulship in 59 BC. Caesar in his ambition

somehow managed to forge a political alliances with both Pompey

and Crassus creating the "First Triumvirate" The Triumvirate

would make Caesar Consul and he would help force through the laws

accomplishing their pu r poses in the assembly. Plutarch 's histories

later quotes Cato as saying that the tragedy of Pompey was

not that he was Caesar's defeated enemy, but that he had been, for

too long, Caesar's friend and supporter.

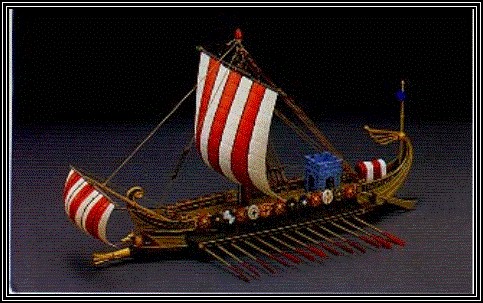

Image Cortesy of the MUSEO TECNICO NAVALE

Image Cortesy of the MUSEO TECNICO NAVALE

Caesar's Consulate brought Pompey the lands and

political settlements he had promised his veterans. Pompey was to

marry Caesar's own young daughter, Julia. Pompey was madly in love

with his young bride. Caesar secured a proconsular command in Gaul

at the end of his Consular year, Pompey was assigned the governorship

of Further Spain. Pompey remained in Rome and govenered Further

Spain through exercising his command of subordinates.

Pompey remained in Rome overseeing the critical

Roman grain supply, Pompey handled the transportation and trade

in grain with his usual excellent efficiency but his success at

political intrigue was less compelling. The Optimates had never

forgiven him for abandoning Cicero when Publius Clodius forced his

exile; only when Clodius began attacking Pompey was the great man

persuaded to work with others towards Cicero's recall in 57. Once

Cicero was back, his usual vocal magic helped soothe Pompey's previous

unfavorable political position somewhat, but many still viewed him

as a traitor for his alliance with Caesar. Other agitators (including

Clodius) tried to persuade Pompey that Crassus was plotting to have

him assassinated. Rumor (quoted by Plutarch) also suggested that

the aging conqueror was losing interest in politics in favor of

domestic life with his young wife. He was occupied by the details

of construction of the mammoth complex later known as Pompey's Theater

on the Campus Martius; not only the first permanent theater ever

built in Rome, but an eye-popping complex of lavish porticoes, shops,

and multi-service buildings . Within this architectural complex

also happened to be the location where Caesar was to be assassinated

in 44 BC.

This text is a partial extract from the web site

Gnaeus

Pompeius Magnus, 106-47 BC written and edited by Suzanne

Cross © 2001. All Rights Reserved. The copy has been rewritten

and modified to explain the historic context for the minting of

the coins with the images of Roman Ships.

To view additional images of Roman Ships please visit.

GALLERIA NAVALE (in Italian) - Roman Naval Gallery:

A selection of Roman naval images

(frescoes, mosaics, bas-reliefs, sculptures, coins and other findings)

published on «Classica» or on the Net.

[GALLERIA

1] - [GALLERIA

2] - [GALLERIA

3]

[GALLERIA

4] - [GALLERIA

5] - [GALLERIA

6]

Previous |

Next

| Table Of Contents

|